- Home

- Anupam Arunachalam

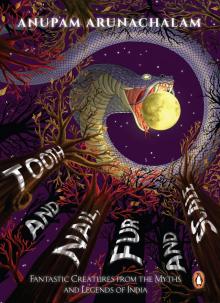

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale Page 11

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale Read online

Page 11

She hoped she would never have to again.

‘There’d be plenty of it for everyone on the ground, dunderhead, if it weren’t for your dumb animals! You want to feed your cows the fruit, you pluck them from the trees!’

Kannan made a rude gesture at her, swatted a patch of grass with his mundu and lay down in it. ‘The cows are giving better milk ever since I first fed them these things,’ he said. ‘Thicker, creamier. Everyone’s noticed it. Even the headman.’

Aravind saw Vaani freeze, her eyes widening.

‘And anyway,’ he said, ‘the cows didn’t eat it all, did they? That Mayilvahanan swept away sackfuls of the stuff to sell in the market. And, you know, I heard his wife—’

‘I’ll take care of his wife, and I’ll take care of you, you scrawny little thief! This is my grove, and these are my fruit!’

Kannan stared at Vaani for a while and then broke into raucous laughter.

Aravind watched Vaani turn bright red. Her eyes snapped to slits and he leapt forward to grab hold of her—but it happened too fast.

Vaani’s scream followed her atop Kannan, who went down like a sack of potatoes. He had three angry red welts on his cheeks before he had the sense to cry out. His hands flailed desperately in front of his face, and he caught her forearms just as Aravind took hold of her waist and pulled her off him.

It would’ve been a good match: Kannan, skeletal and uncoordinated but with an overall advantage in height, age and low cunning; and Vaani, thick of limb and fast as lightning, but shorter and predictable. Aravind might have had a tale to tell the next day, when the panchayat discussed the unprovoked attack and condemned the grown man who’d hit a girl.

But a shriek rang out from the far edge of the grove, freezing the scene.

The three raised their eyes, still tangled in the grass, and saw Mani, Mayilvahanan’s eight-year-old nephew, leap over a bush.

‘AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHH!’ he screamed, barrelling at them. They pushed each other away and tumbled to either side as Mani ran through the narrow gap between Kannan and Vaani and straight out of the grove.

For a long moment, they just lay there, blinking at his after-image.

‘What the—’ began Kannan after a while, picking himself up and immediately wincing at the pain in his face and chest, where Vaani had dealt him blows.

‘What was that all about?’ asked Aravind. Vaani shrugged at him and jumped to her feet.

They joined Kannan in the middle of the grove, where he stood frowning, looking around at his cows.

‘What’s wrong?’ asked Aravind.

‘Where’s my cow?’ asked Kannan, glaring at his herd. ‘The one you smacked. It’s missing!’

‘What does that have to do with—’

‘If something’s happened to Velamma, I’m going to kill you!’

‘What do you mean, something’s happened—’

‘She ran in the direction the boy came from. If she’s come to harm, I’ll—’

‘Look, we should get out of here,’ cut in Aravind. ‘Whatever Mani saw, it scared the pants off of him.’ He began pulling Vaani away towards the village, towards safety.

‘I’m NOT going anywhere without all my cows,’ said Kannan, stalking off in exactly the wrong direction. ‘They cost me Rs 20,000 apiece!’

Vaani shook free of Aravind’s grip. ‘Don’t be a wuss!’ she told him. ‘Mani’s a known coward. We should check this out, whatever it is.’

‘It might be a leopard!’ said Aravind. ‘A tiger, even!’

‘That’s impossible,’ said Vaani simply and took off after Kannan. ‘There aren’t any wild animals in this grove.’ It was true, Aravind reflected. In the past two weeks, he hadn’t seen a single wild creature around the fruit trees. Not even birds or insects.

They crossed to the edge of the copse, where the underbrush claimed the forest again, and began wading through it.

‘Well, we aren’t in the grove any more,’ said Aravind. ‘There’ll be snakes in the bushes for sure!’

But Vaani didn’t seem to hear him. Kannan had disappeared into the foliage, and they could hear him calling for Velamma.

‘Are you an idiot?’ said Aravind, projecting his voice into the distance. ‘A cow wouldn’t go through here!’

‘AAAAAAAAAAH!’ came Kannan’s reply.

The two froze for a moment, the blood chilling in their veins, before Vaani chased after the scream and Aravind had no option but to follow.

Tearing out of the undergrowth, they almost broke their faces on Kannan’s shoulder blades, and had to hold on to his arms to stop themselves. He didn’t object. He didn’t even move. His skin was clammy, and his muscles taut.

Vaani screamed as she peeped from over Kannan’s shoulder, and Aravind joined her when he saw what they were looking at.

They had come upon another grove. The grass here was wild, but only shin-length, and green as fresh moss. The fruit trees stood tall here—much larger than the ones they had seen before—and the produce was far more plentiful—in clusters between the leaves and in mounds upon the grass. Their roots were thicker, the dripping sap pooled around them. The scent of the fruit—sweet and fulfilling—and the sweaty whiff of the slime made for a heady mix.

And in their midst was what used to be Velamma the cow.

At first, Aravind thought the animal was caught in the foliage and was struggling to extricate itself. Then he realized that the cow wasn’t moving of its own volition at all. The roots and branches were dragging it back.

They had wrapped themselves tight around its legs and wound around its torso and neck, forcing its mouth open. Then they had entered through the maw and broken out of the ears. Or perhaps it had been the other way around—he couldn’t tell.

‘Look,’ whispered Vaani, pointing at the ground, where a trail of slime and disturbed grass ran from the edge of the grove to the foot of the tree.

‘Run,’ Aravind said and, lifting Kannan’s rigid body by the armpits, they pulled him back into the forest proper. They skirted the edges of the first grove and ran all the way back to the village, stumbling and staggering, but never stopping.

They came back the next day, this time with twenty men and women, armed with axes and blazing torches. Even the stench of kerosene, which had stayed with them all the way from the village, couldn’t overpower the bittersweet aroma of the grove.

The cow had been digested. Mostly. The roots and branches had pulled it higher now, entwined in its ribcage and pelvis, from which strips of flesh hung bloodlessly. Its head stuck out from the pool of slime, fixing them with a glassy stare.

‘Burn it,’ ordered the headman, inverting a can of kerosene on to the slime. It formed a rainbow film on the surface and when the match fell into it, caught fire readily.

The roots burned silently, without any fuss, and eventually the men worked up some courage and started hacking the branches off with their axes. The next day, a few of them would notice bright-red weals down their forearms, but now none of them saw the trees acting up—or, in fact, acting out of the ordinary at all.

The village sent search parties deeper into the forest—as far as they could safely go—to find out if there were more of these trees. Kannan went with them, seeking revenge for his beloved (and expensive) Velamma. Aravind and Vaani were sent home early, and didn’t speak to each other for days. Through it all, Aravind kept a shameful secret—he still missed the taste of the fruit.

For months after, cars would stop at Mayilvahanan’s shop on the highway and ask his wife about the fruit. It had become some sort of a sensation on the Internet, apparently. But the headman had ordered all the fruit burned, and so they went away disappointed.

A week and a half after the incineration, Aravind knocked on Vaani’s door and was let in by her mother, who looked much more fidgety than usual. She told him to sit in the front room and went to get the girl.

Vaani appeared in the doorway a few seconds later and stood there, studying the boy.

; ‘You haven’t been coming to school,’ said Aravind.

‘Wasn’t well.’

‘Well, you look all right today. Isn’t your mother telling you to go?’

Vaani shrugged.

Aravind waited for an explanation and then walked up to her. She backed away.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asked, leaning in, as if she had a secret to tell him.

She leaned back. ‘Nothing. You can go now. I might look all right, but I’m sick.’

Aravind craned his neck into the doorway, took a couple of sniffs to be sure and then, pushing her aside, barged into the house.

‘You can’t go in there!’ said Vaani.

‘Where is it?’ he asked, bursting out into the backyard, casting about, his hands clenched into fists. ‘Where’ve you put it?’

She pulled at his shirt, tore the sleeve half off, but Aravind wouldn’t stop. Her mother stood watching, transfixed, a moral uncertainty on her face.

Finally, he noticed the pantry, with its door closed and bolted. He pushed her away and sprung it open. As it swung on its hinges, he caught the familiar smell of wet earth and the fruit and the slime. He stumbled back, grimacing, and turned away.

The floor of the pantry had been packed with mud at least a foot high. The size of the tree had shocked him—he had expected a sapling or at best, a flowering plant, not a developed trunk with a head of golden leaves and a wet beard of roots.

Vaani closed the door silently as Aravind hurled on her floor.

‘It doesn’t need sunlight,’ she said by way of explanation.

‘Blaaaargh!’ said Aravind.

‘I never forgave you for telling them the first time,’ she said. ‘You told them about my grove. My trees. My fruit. And they ruined it.’

‘It’s—’ he began, and retched again. ‘It’s . . . it’s an—abomination!’

‘It’s harmless,’ she said. ‘Completely harmless to humans. It only eats animals.’

‘You knew!’ he said. ‘You knew before it killed the cow!’

She brought a bucket of water from the kitchen, a washcloth half dipped in it. ‘I went up one of those trees once,’ she said. ‘I wanted to see how the fruit tasted raw, so I climbed up the branches.’

‘Oh, God.’

‘The birds are attracted by the smell of the fruit, I guess. Their wings probably get slathered in the slime, and then the branches grab them.’

Aravind heaved, but there was nothing left to come up.

‘And there were insects. So many of them. I think it was saving them, for a dry spell.’

‘Please! Stop!’

‘That’s why there were no animals in the grove.’

‘Oh, God. Vaani, please!’

She kicked the bucket towards him, splashing water on his school shoes. ‘Clean up your mess,’ she told him. ‘And get out.’

Aravind wiped his mouth, shot her a grimace and turned towards the door.

‘If you betray me again, I’ll kill you,’ she said. ‘It’s my tree. My fruit. And if you don’t like it, all you have to do is stay out of my house!’

She called him names as he left the house, and followed him with her eyes as he went up the steep road that led to the school. He turned around just before he went over the hill and saw her still at the door, looking at him as she sunk her teeth into one of her fruits.

COW-EATING TREE

The Pili Mara or tiger tree is a carnivorous plant like no other. While the Venus flytrap and the pitcher plant content themselves with dining on insects, the Pili Mara hungers for entire cows.

In 2007, in the village of Patrame in Karnataka, a girl claimed she had seen a tree attempting to eat a cow. According to her, the tree had grabbed the animal’s hindquarters with its branches, lifting it off the ground. A man working on a fence nearby answered her calls for help and began lopping offits branches, but the tree wouldn’t let go until it had been completely chopped down. The cow finally escaped with a sore tail.

A farmer from the area reported that there had been a similar incident in the village thirty years ago, with a similar resolution. Both these trees were of two different commonly known varieties, so the scariest part of all this is that you can’t tell which tree might suddenly develop a taste for beef!

THE WRITING ON THE WALL

One important thing to note is that this was before all this IT city nonsense—before all this traffic and pollution and the chemicals in our water, okay? This was when Bangalore really was a city of gardens and lakes. And if you think the weather here is good now, well, beta, you would’ve refused to leave only back then.

I was thirteen the year the Naale Baa bhootam came to Bangalore. They’d heard about it in north Karnataka before that, and in parts of Andhra, but as I was only thirteen when I started hearing the words ‘naale baa’ being whispered in the corridors and the classrooms, I didn’t know what on earth it meant.

Somehow it took three full days for the details to percolate to my circle of friends. Now, I wouldn’t say I was in the popular crowd in school—with all the cricket champs and the rankers—but I wasn’t on the bottom rung either. So it’s surprising that news of such importance took so long to come to me.

I think the first person to give me any real information must have been Amrita, one of the fifteen kids with whom I rode to and from school in an old Tempo Matador. TT Krishna and I listened to her, rapt, as she hissed over the rattling of the engine.

‘It’s a witch,’ she said in response to our questions about whether she knew what this Naale Baa thing was. From the few tatters of information we’d snagged, we’d gathered that it was some kind of a monster—a ghost or a serial killer or something like that.

‘A witch?’ TT said. ‘But witches are only in the villages, no, Akka1?’

‘No, you idiot. Just sit quietly and listen.’

‘Ya, idiot,’ I said. ‘Witches can come anywhere. They have brooms, no, to fly on?’

‘Shut up, Subbu,’ said Amrita, her irritation forming cute wrinkles on her shapely nose. ‘She’s not one of those broomstick witches. She doesn’t cast spells and all. She straightaway kills you off.’

‘Oh!’ said TT and I.

‘Ya. So be alert, okay? Don’t open the door for anyone at night—even if you know their voice!’

‘Why, Akka?’ asked TT mindlessly.

‘Because she can mimic anyone’s voice, da! She can come as your paati2 or she can come as the neighbour uncle. So just to be on the safe side, don’t open the door and ask them to come in the morning.’

‘But what if it is my paati?’

‘Tsk,’ uttered Amrita. ‘Then look through the peephole. If you see her, you can open it. If you see the witch, just go inside and hide.’

‘What will she look like?’

‘She’ll look like an old woman—and she’ll be dressed in ragged clothes. She has long nails, which she’ll use to slice open your neck if you open the door.’

‘But my paati is also an old woman, Akka!’

Amrita rolled her eyes and leaned back in her seat. I knew we had lost her then, because of the idiot TT and his stupid questions. Our one good source of information, and we’d bungled it. She wouldn’t tell us anything more, no matter how much we pleaded.

But I need not have worried. The whole thing went from being a bunch of secrets to public knowledge by lunchtime the next day.

Of course, the burning question was why Naale Baa? I mean, ‘naale baa’ in Kannada means ‘come tomorrow’. Why was that the name of the witch?

I asked Senthil as we were walking back from the football field after the lunch break.

‘Oh, you don’t know?’ said Senthil, stopping short in the middle of the corridor. ‘It’s the protective charm that saves you from her.’

‘Huh?’

‘Ya. If you want to be safe from the witch, all you have to do is write “naale baa” on your door, and she’ll look at it and won’t bother you.’

‘She’ll read the

sign and return the next day? And then she’ll read it again, and then—’

‘You get the drift.’

‘Wow . . . why not write “come never” or something? Why “come tomorrow”?’

‘Ya, why don’t you try that, da?’ he said, suddenly turning frigid. ‘You try, and if you’re alive the next day, we’ll all do that, okay?’ He strode away in a huff, leaving me to ponder my lack of social graces.

In class, Kamini Kumar was saying that her friend Srilekha had heard the Naale Baa bhootam calling for someone who lived in her neighbourhood—knocking at night and begging to be let in.

‘The next day, Srilekha saw that her neighbour aunty had been murdered!’

‘WHAT? She saw her dead body?’

‘Are you crazy? No! She only saw the white tent outside the house.’

‘How much blood was there?’ I asked, imagining a white tent with red splattered all over it. ‘Did she see it when she was passing by the house?’

‘They would have cleaned it up, no, duffer? But she heard that there was a lot when the newspaper man found her in the morning collapsed in the doorway of her house, her head cut off clean.’

‘Wow. And all because they didn’t write “naale baa” on their door,’ said Sushil, the class monitor, solemnly.

People were falling to the witch all over the place. Only a week after Srilekha’s neighbour aunty incident, our history teacher, Prakash Sir, suddenly stopped coming to school. The substitute teacher told us that he had moved to Bombay, but soon word got around that it was just a cover story to keep us from panicking. Prakash Sir had been taken by the Naale Baa too. In fact, his whole family had been brutally murdered because they hadn’t written ‘naale baa’ on their doors.

When I got back home that night from music class, I found the legend of the Naale Baa had crossed generational barriers. My parents were talking about it in what I have to say was a very callous manner.

‘Apparently, there’s a witch, and she’ll come to kill you, but you write a few instructions for her on your door, and she’ll quietly go away,’ Amma was saying, a big grin on her face.

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale