- Home

- Anupam Arunachalam

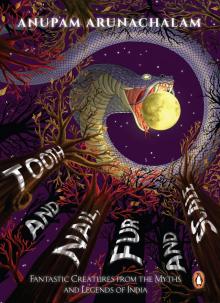

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale Page 10

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale Read online

Page 10

The door swung open, and her mother stood with her arms outstretched and a big white smile. Usually, Latika would run into her embrace, but this time, she waited for too long and her mother lowered her arms. ‘What’s wrong?’ she asked, her eyes wide with concern.

‘You—you’re late.’

‘Yes . . . I was caught up with some business . . . an unruly wolf pack.’

Latika eventually put her arms around her mother’s waist and buried her face in the sari, which was just starting to take on her mother’s sharp tang.

‘Is there . . . something else?’

‘No.’

‘Shall we eat then?’

They sat down for the meal, and Latika snuggled up to her. Her mother was clumsy—she let the rice dribble from her hands as she fed her—but Latika didn’t mind.

‘The meat . . . tastes wonderful,’ she said.

Her mother smiled. ‘I knew you’d like it. I had some trouble separating that deer from the herd—but I knew it would be worth it in the end.’

Latika looked up at her, open-mouthed. ‘How does it feel to . . .?’ She snapped her teeth around the question, cutting it off.

‘How does it feel to . . . what? Chase the deer?’

‘No . . . I just . . . I was going to . . . no—nothing.’

‘What’s wrong, my love?’

Latika desperately looked for another subject she could pounce on. Something significant, but just different enough. ‘I was . . . the other kids at school . . . they say Father does witchcraft . . .’

‘Do they, now?’

‘They say he’s a savage, and that he’s married to a dark spirit.’

‘And?’

‘And . . . and—I don’t know. They say his wife is a monster who turns herself into a beautiful woman . . . with amber eyes and long black hair and smooth copper skin. They say I’m a half-breed.’

‘Hmm. Did you talk to your father about this?’

‘I—yes. He told me not to believe them. That he doesn’t know any magic. He said if he knew magic, we wouldn’t be living in a small hut near the forest.’

‘So there you have it.’

‘And about you? Is what they say true?’

‘Well, I’m no spirit, nor a monster.’

‘Is this . . .’ She touched her mother’s skin, which was a bit lighter and ruddier than her own flesh, but not really the colour of copper. ‘Is this your true form?’

‘It’s one of my shapes. It’s not glamour or illusion.’

‘And your . . . other form?’

‘You’ve seen it, Latika.’

‘Yes.’

‘And is it monstrous?’

‘No. It’s beautiful. Not scary.’

‘No. Not for you.’

‘You still look like you—like my mother.’

‘So there you have it.’

‘What is it like to—’ Latika stopped short again.

‘What is it like to be a tigress?’

Before she knew it, Latika was sobbing uncontrollably into her mother’s bosom. It was partly because she knew she couldn’t keep the secret as her father had instructed, and partly because she didn’t want her mother to leave tonight. She wanted to be held as she was being held now, and rocked, just like this, a whole night long.

‘Hush,’ her mother said, stroking Latika’s hair with her customary gruffness. ‘Stop crying, and tell me what’s wrong.’

Latika didn’t think she could ever stop, but her mother suddenly gripped her under her arms and ripped her away from herself. It surprised the sobs out of her as she hung at arm’s length, staring straight into her mother’s eyes.

‘Don’t be mysterious, like these people,’ her mother said. ‘Don’t hide your thoughts behind these emotions. Tell me.’

‘But Father said I shouldn’t. He said I shouldn’t tell you. He made me promise!’

Her mother let her go and gazed at her thoughtfully. ‘Well, how about if you . . . show me,’ she said, finally.

Latika stared at her, befuddled.

‘He didn’t make you promise not to show me,’ her mother said again.

The sudden introduction to this new kind of deception knocked her off balance. Latika quickly debated the ethics of it, failed to come to a conclusion and made a decision nevertheless. ‘It hurts,’ she said.

Her mother grabbed her in a tight hug. ‘I know,’ she whispered, ‘I know, my dear.’

When she broke free from the hug, Latika found that her mother was smiling, and that her eyes were brimming with tears. Her voice was tremulous when she spoke. ‘But it’ll hurt less each time you do it, and finally, it’ll be just a little jolt—more in your heart than in your bones.’

‘Okay. I like doing it, though. Father told me never to do it, but I can’t—I don’t think I can stop.’

‘Why should you?’

Standing up, Latika went to the centre of the room and undressed. Her mother stood with her fist pressed to her mouth and nose, watching her little girl get down on all fours.

Latika thought about her nose and jaw elongating, about her hands and feet lengthening, the fingers and toes coming together, popping claws. Pain flashed along her spine and ribcage as her shoulder blades were prised apart and angled towards her flanks, and muscles blossomed down her arms and legs. Her senses changed as fur erupted from her skin—the smells of the masala in the food were suddenly too much, the sounds of the forest resolved into meaningful signals and the room became confining, alien.

‘Beautiful,’ breathed her mother and sprang to her feet. She cast off the sari as she bounded out of the back door. Latika followed her, and watched her leap away on a woman’s legs but come down on paws. She felt an unspeakable thrill as they tore into the forest and, though the cold couldn’t cut through her fur, the feel of the wind sent chills down her spine. They ran together between the trees, two streaks of fire in the black night.

Latika caught the scent of prey, diminishing rapidly as they stormed through the foliage. Her ears were full of the indifferent buzz of insects on the wing and the quickening pulse of birds in their nests and hollows. Her mother would glance at her proudly from time to time, and Latika knew that what seemed like a race to her was really only a languid trot for the experienced adult.

Latika was ravenous, but didn’t know how to show it. She purred and chuffed, but her mother didn’t seem to notice. She caught a whiff of something appealing darting to the right, and ducked through the underbrush to follow it.

She didn’t know that her mother had been following her until the adult tigress landed on top her, snarling. Latika growled, struggling to get out from under her, but it was of no use. After she had submitted, her mother turned around and led her back to the path.

They stopped at a watering hole, scattering the monkeys clustered around it. While Latika lapped at the pool, her mother dashed off into the trees. She returned before Latika’s thirst was quenched, dragging a wild pig by the neck. Setting it down a few feet away from the water, she began to pluck it. Latika followed suit, pulling out tufts of the creature’s fur.

But before she knew it, she was tearing into the carcass, gobbling its innards.

Once they had washed, her mother changed to her human form and prompted her to do the same. ‘You can’t hunt on your own,’ she said. ‘Not before I show you how. You’re too loud and too slow.’

Latika nodded, wondering why it had seemed so natural to feast on raw flesh as a tiger while it sickened her to think about it now.

Her mother skipped a stone across the surface of the water, chuckling softly. ‘This is where I met your father for the first time,’ she said. ‘He was brave and beautiful, and he almost put an arrow through my eye.’

Latika gasped.

Her mother laughed. ‘To be fair, I’d just tried to rip his throat open!’

She told Latika about their early days, when she had gone with him to live in his world and had entertained the idea of leaving the forest behind. Of l

iving as a woman forever.

‘But you couldn’t do it,’ said Latika.

‘I might have. If it hadn’t been for the man-eater, I might well have. But I couldn’t risk its presence—not with you just having been born. The men with guns couldn’t catch it. It was too sneaky for them.’

‘But not for you.’

‘No.’

‘And then?’

‘Once I changed back, once I returned to the forest, it was hard. First, there was the thrill of winning my place in the wild again. It took months in human time, during which I went back to your father less and less. He was so angry, because he knew it wouldn’t last much longer between us.

‘It’s difficult making your place in the world when you’ve been gone as long as I had. I had to announce myself to every herd—it took a lot of effort to make my presence felt again. I had to spray my scent all over the forest again, scratch every tree that looked like it had been rested against by some other predator. They rallied against me, the wolf packs, the elephants, an old black bear in his desperation . . . but then I had the advantage of being able to see the bigger picture—of being a woman as well as a beast.’

They smelled the fire long before they saw it, and hugged the ground as they cleared the trees.

Her father sat in the yard, his back to an enormous bonfire, his hand curling and uncurling around an unlit torch. His bow and arrow lay beside him within easy reach, and his hunting knife hung at his waist.

Her mother showed herself first, a low growl on her lips. Her father jumped to his feet and, with a practised move, waved the head of the torch into the flames, firing it up. He held it aloft, careful not to let its light blind him, should he need to act fast.

‘You took her!’ he bellowed, saliva flying from his mouth. ‘You did the one thing you promised never to do!’

Her mother circled the bonfire, the grass brushing her belly.

‘You took everything from me. And now you took the only thing that remained!’ he spat.

Latika cowered in the bushes, the fire making her very, very nervous. Its smell was toxic, its heat made her skin crawl. But what was scariest was her father’s stance—feet apart, bent at the knees, one hand clutching the torch, the other hovering near the knife.

‘Go!’ he said. ‘You’re not welcome in my house any more!’

Her mother roared, making him back away, closer to his bow, closer to the fire.

‘Go!’ he said still, brandishing the torch, and Latika noticed that he was crying freely. Tears streamed down his face and heavy sobs racked his body.

Her mother reared up and turned smoothly so that she was standing upright by the time she was a woman, her chest thrust out in pride and resistance.

‘You made her promise not to tell me!’ she said. ‘How dare you try to keep this from me?’

He sat himself back down on a rock and flung the torch into the flames.

‘It is her nature to be a tigress. You cannot take it away from her!’ she said, raising her voice.

‘Just as I couldn’t take it away from you.’

She didn’t reply. She looked at Latika and gestured for her to come closer. Latika changed, whimpering from the pain, and ran over to her father, throwing her arms around his neck.

‘I’m sorry, Father!’ she cried. ‘I’m sorry! I shouldn’t have gone, but I didn’t have a choice! I couldn’t not tell her. I couldn’t not change!’

He hugged her tight and kissed her cheeks. ‘I know,’ he said. ‘I shouldn’t have tried to stop you. It’s not your fault.’

Her mother watched from a distance, still a woman holding that defiant stance.

Her father looked up at her and nodded. ‘She can’t miss school,’ he said. ‘That’s where she learns what it is to be human. Not because they teach her from those books, but because she mingles with the others, learns their ways. Something I never really got used to, despite being a man and nothing else.’

Her mother gave him a begrudging nod. ‘I won’t take her away from you,’ she said, her voice still firm.

‘You will,’ he said. ‘Just . . . not yet.’

‘No, she won’t!’ said Latika. ‘I’ll always be your daughter.’

He sighed, held her close and put his mouth to her ear. ‘That’s what she said,’ he whispered. ‘That she would always be my wife. But the jungle took her back.’

‘It won’t happen that way with me,’ said Latika, summoning all her determination, and hugged him again fiercely.

When they turned, her mother was nowhere to be seen. For a moment, Latika was filled with a great fear, but her father said, ‘She will be back tomorrow.’

‘How do you know?’ Latika asked.

‘Because she could never leave you,’ he said.

And he carried her back into the house, where the meat cooked slowly on embers and the smell of spices hung from the walls.

WERETIGER

Several cultures in India believe in weretigers—men and women who can transform into tigers at will. The Kandha people of Odisha believe that some among them have been blessed with this power, and that they turn into tigers to wreak vengeance upon their enemies.

‘There was a man around here whom we knew to be a shape-shifter,’ my local acquaintance had once told me as we sped along the dark highway that wound its way through the forested hills of Kandhamal. ‘A tiger was shot in its paw, and when the hunter got back to the village, he saw this man bleeding from his hand!’

Weretigers are regarded with a reverent fear and are said to be harmless to those whom they consider friends.

THE VEGETARIANS

‘I don’t care! I found it, so it’s mine!’ Vaani said, her face red with fury.

‘Wow . . . you’re a real dolt, you know? A greedy little dolt,’ said Aravind, and got a smack on the shoulder.

As they walked down the hill towards the treeline, an empty jute sack swinging in each of their hands, Vaani stared at the village nestled in the valley below, frowning.

‘Could we go a little faster?’ said Aravind. ‘If we don’t hurry, Kannan will have taken every fruit that’s on the ground, and we’ll have to climb up one of those yucky trees to get our share.’

‘I don’t care,’ said Vaani. ‘I’m going to take this to the panchayat. You know Mayilvahanan’s been selling the fruit at his stall now?’

‘Yeah, of course. My mother bought half a kilo from him on Wednesday.’

‘Not in the shop in the market! In his tender coconut stall on the highway, the one his wife runs.’

‘Wha—really?’

‘Yeah. She has a sign up saying the first one is free, after which it’s a hundred rupees for a single fruit! And she returns home every day with her baskets empty and her purse full to bursting!’

‘But the headman said—’

‘Exactly. And this guy, this Mayilvahanan—he thinks he can take MY fruit, and sell it illegally to outsiders!’

‘It’s not illegal, technically. The headman can’t really decide what’s legal and what’s not.’

‘It’s the rules! Whatever the headman says is the rules!’

‘Okay, okay . . . stop getting so worked up. What do you plan to do about it?’

‘I’m going to tell the headman about him! And about this Kannan and his darn cows! How can he waste the fruit on cows, for God’s sake? That’s worse than illegal! Th-that’s . . . sinful!’

‘Keep your voice down! He’ll hear us,’ hissed Aravind as they crossed the first stand of trees.

They jogged down a narrow dirt path that wound through the copse and the underbrush. Three weeks ago, when he had first followed Vaani into the grove, it hadn’t been there. Since then, everyone and their grandmother had been making multiple trips here every day, beating the scrub into submission under their feet.

They saw the first cow a few feet before the grove proper, dopily chewing the cud. Vaani curled her upper lip in disgust, and gave the bovid a resounding slap on its rump as she passed it.

It fled into the trees, bellowing.

‘What did you do that for?’

‘It was eating my fruit.’

A nearby cluster of oleanders rustled and spit out a man so skinny you could count his ribs. Kannan the cowherd wore a mundu1 around his head like a turban, and long white boxer shorts with vertical blue stripes.

‘What was that!’ he screamed. ‘What did you do to my cow?’

‘What was your cow doing here, you bag of bones?’ said Vaani.

‘Yei-yei-yei! Fatty, I’ve told you already! My cows go wherever I go, and I choose to go right here to graze them!’

‘They’re finishing all the fruit, you idiot,’ said Vaani. ‘There won’t be any left for us soon if your dumb animals eat everything!’

‘Yei-yei-yei!’ said Kannan, whipping the mundu off his head and knotting it around his waist in one quick, aggressive motion. Vaani leapt back, startled by the sudden movement. ‘Cows are like our mothers, fat girl! They deserve the best, and nothing but!’

Vaani shouldered him as she strode into the grove, trailing Aravind, who’d been frowning pointedly at the seething cowherd.

‘Look at this!’ wailed Vaani, gesturing with her arms outstretched, palms up. ‘There’s hardly any left!’

She was right. The cows seemed to be ignoring the grass completely, instead going exclusively for the fruit that had dropped to the ground—swallowing them whole, and licking them up if they were splattered.

‘There are plenty up there,’ said Kannan, pointing to the trees. ‘Some climbing will do you good. Take some lard off your middle.’

The trees were not that tall, and Vaani knew that she could climb them if she wanted to. Their flat, golden-brown long-bladed leaves were clustered so thick that the gold was interrupted only by the red of the fruit. The branches themselves could hardly be seen. The roots hung from them like a banyan’s, but they were slimy with clear sap, the same kind that bled from the cracks in the bark and coated it. You could hold on to the vines, plant your feet in the trunk and go up pretty easily. Vaani had done it once.

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale