- Home

- Anupam Arunachalam

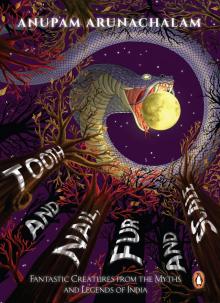

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale Page 18

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale Read online

Page 18

I kept my bow in one hand and plucked out the arrows, starting from his tail. When I removed the twenty-second arrow, the one that would release his head, I nocked it in my bow and pointed it at him.

He was breathing hard when he turned human again.

‘Okay,’ I said, ‘start talking.’

‘I’ve heard of you,’ he panted. ‘You’re the archer without the thumb—the Nishada prince, who—’

‘Yeah, good job, pal,’ I said. ‘You got me. Now tell me something about this fine situation that we’re all caught up in.’

He stared at me for a while, as if he was trying to commit my face to memory, and then said, ‘Well, if you haven’t realized it yet—you’ve been lied to.’

‘I haven’t realized, no.’

‘Okay, okay. I don’t think we have the time to argue about this, so I’ll tell you exactly who I am and what I’m doing here.’

‘Finally.’

‘But you have to understand . . . everything I’m telling you—’

‘Is confidential. I know. I won’t breathe a word about it. And if you’ve heard of me, you know I’m good for it.’

‘I work for King Vasuki’s spymaster,’ he began. ‘And two weeks ago, I was tasked to rendezvous in Girivraja with an emissary from Amaravati.’

‘Hold on. Vasuki’s the king of the nagas, right? And by Amaravati, you mean—’

‘The capital of Indra. In heaven, yes. I was to pass on a certain report to this emissary, about weapon stockpiling and troop build-up in the realm of the daityas.’

‘The daityas? Where do they come in now?’

‘Among the seven levels of the netherworld, our realm, Patala, is the deepest, and that of the daityas, Rasatala, is the one immediately above it. Over the past few months, our intelligence network has registered a spike in their military activities. We suspect they’re planning to mount another attack against the devas, since most of the weapons they’re hoarding are specifically tailored to work against heaven’s forces.’

‘Huh. Okay?’

‘We don’t have a formal alliance with the devas, but there has been some mutual support along back channels in the past, so it was decided that we’d convey this information to Amaravati. I was to sneak up to the surface-world and deliver the information at a certain time and place.’

‘And what happened?’

‘The emissary wasn’t at the rendezvous point. I’ve been going back to the same spot at the same time every day, but he hasn’t turned up.’

‘Why didn’t you just go back home?’

‘I thought about it, but it didn’t seem like the wise thing to do. It’s highly probable that the reason the devas didn’t send their guy was that they knew our communications had been intercepted. In that case, it would be a terrible idea for me to head back right away, because I’d have to pass through the realm of the daityas, and they’d be on high alert.’

‘Hmm . . .’

‘And now that I think about what you’ve revealed—that another naga’s set you on my trail—I guess there was a traitor among us all along.’

‘Well . . .’ I said, still trying to process everything he was saying, ‘I guess if we’re dealing with daityas . . . aren’t they shape-shifters too?’

‘They can change their forms, yes.’

‘Then if what you’re saying is true, why haven’t you considered that my client may be one of them?’

‘Wait. Why did you say she was a naga?’

‘Because she told me so!’

‘You didn’t check? You didn’t ask her to show you her true form?’

‘Uhh,’ I said, feeling a bit dumb, ‘she told me she couldn’t transform without her nagamani, which she claimed you’d stolen.’

He gave me a blank stare for about five seconds, and then slowly shook his head. ‘The mani has nothing to do with the transformation.’

‘Huh. That’s seriously messed up,’ I said, but the last couple of my words were drowned out by a banging on the door.

‘Open up!’ yelled my former client, who I now realized was probably a daitya, a traitorous naga or something to that effect. ‘I know he’s in there!’

‘What do we do?’ I said.

‘Is your charm near the door still intact?’ the naga asked.

‘Yeah.’

‘Will it activate if I go out past it?’

‘No . . . it only attacks incoming intruders. You’re planning to go out there?’

‘Open up, or we’re coming in,’ said the voice from outside. I noticed that it had changed just a bit. Become slightly rougher around the edges.

‘What does she mean, we?’ I asked.

‘There are three of them,’ said the naga spy. ‘I can sense their magic. That’s why they sent you after me, so that I wouldn’t sense them and go deeper into hiding. They probably thought they could follow you to get to me, but I made it even easier by coming to you.’

‘You can’t go out and face them,’ I said. ‘Can you?’

‘Can I beat them? No. But I could buy you some time.’

‘Buy me time? To do what exactly?’

‘Does this place have another exit?’

‘Through the back.’

‘Get out. Hurry. Find someone who can commune with the devas, or with the nagas. I’ll hold them off until you get away.’

‘What—what’ll they do to you?’

‘They’ll kick me around for a bit. For a lot, actually. But they won’t kill me. They need me alive to prove that we were conspiring against them with the devas.’ He nudged me towards the back room. ‘Get out. With any luck, there’ll be deva spies watching Girivraja for exactly something like this. They might be able to find you.’

‘But if they’re watching this, they’ll already know—’

‘The daityas will have conjured up an occluder field around this place to make any disturbances harder to detect. Standard procedure in counter-intelligence.’

The banging at the door became louder. And I figured the only reason why my client hadn’t straight up broken the door the first time was that she’d seen me put the charms on it.

I looked at the supplies I had crammed into my shelf, and then at my bow. ‘I can help fight them off,’ I said. ‘A warrior priest once showed me how to make my arrows effective against magical—’

‘It’s no use!’ said the naga. ‘Get out and tell someone about this! That’s the best way you can help right now! Get word to Indra!’

Just as he said the last word, the door blew into smithereens, and I had my first good idea of the day.

‘Give me your mani!’ I told the naga, ignoring the massive hairy shadow framing my door.

‘Why?’

‘I’m going to use it to send a message! Give it to me, quick!’

‘Come out here, naga spy,’ said a guttural voice from the doorway. ‘Let’s settle this here and now!’

‘Are you planning to use the mani in the fight?’ I asked.

‘No, but—’

‘Then give it to me! At the very least, it’ll be safer inside the house!’

He grimaced, torn between decisions, and then put a hand to his chest. His face twisted with the pain and the effort of ripping it out, and just before it came away in his hand, he screamed the most chilling scream I’d ever heard.

The mani was slick with his blood and tissue when he handed it to me. I started to say something stupid to try and soothe him, but he’d whipped around and dashed at the figure standing at the door, ramming it out of my house with his shoulder.

I ran into the back room and got busy.

If I was asked to name one thing I am good at, I’d say it’s learning. I mean, sure, I was known for my archery once, and I’ve been making a name solving weird, stubborn problems on a freelance basis for a while now, but the thing that has made it all possible is that I am good at learning new stuff really fast. This is partly because of my memory, which is just short of perfect, and partly because I love the proces

s so much. I’ve never come across a piece of knowledge that I could be sure was useless . . . Have you?

In fact, the reason I’d come to Girivraja, the reason I was in this line of work, was that it offered more learning opportunities than anything else I could think of. Some day, I’ll have to go back home and govern a nation and command armies, and those are big responsibilities. I’ve been groomed for them since I was born, and I’ve been trained for them exhaustively. But there are some things about ruling and warring that can’t be learnt by doing just that. There are some aspects of these roles that may be better imbibed by doing other things.

Every piece of coherent information is like a puzzle piece, and you never know when you’ll find a bunch of other pieces that’ll fit snugly with it, revealing a bigger picture.

What I’m trying to say is that when I set out to perform the installation ritual for the nagamani in my house that night, I wasn’t just calling upon the memory of watching the pandit perform it that morning. I was calling upon everything I had ever learnt about rites and sacraments, magic and power. Every connection I’d made between these things now led to new links, and every link to new realizations.

But of course, I still didn’t know whether it would work.

I lit a cooking fire with what little firewood I had lying around and drew a mandala around the gem with the burnt end of some kindling. I annotated it with ash—just the normal sort, lacking the variety considered sacred. The offerings to the gods were mostly regular items found in any well-stocked pantry, but I didn’t have a well-stocked pantry and so I filled the nine-cell grid with substitutes that I hoped would do. I put some ghee in a bowl and dipped a spoon in it, bringing out a container of water for the ablutions.

Whatever else the pandit had chucked in the fire was way too exotic for me to have on hand, so I prayed that what Adridev had told me about most of them being irrelevant was true.

I began chanting the mantras.

Outside, the battle raged, and I tried not to think about it. The blows traded came thick and fast, accompanied by blood-curdling screams of aggression and agony that couldn’t be mistaken for human voices. Plumes of dark mist rose outside my window, and I heard them singe the combatants’ skin. The night was lit up by flashes of blinding light, and explosions followed. I had to raise my voice over the ripping and raking and slashing, and hoped that the foul blood splattered through the shutters and into my room wasn’t desecrating all my efforts. Rubble rained on me when they tackled each other to the ground, and fissures ran through the floor.

I was surprised when it suddenly stopped, and terror gripped my heart when I realized that the naga spy could not have won. I struggled to focus, worrying that my tongue would slip up on important incantations so close to the end, rendering the whole process worthless.

The first daitya who came through the door shrieked as he was zapped by the charm at the entrance and fell backwards. The one behind him shoved him back in, letting his body take the brunt of the spell, and used him to smudge the crude lines of rice flour. She trampled him as she charged in, calling out my name, and I knew that this was the one who’d got me into this whole thing that morning. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw that she was dragging her left leg as well as covering her right eye with one hand. Her other hand was wrapped around the neck of the naga spy, who hung limp from her grasp.

I struggled to pronounce the last syllables of the final stanza, having run out of breath, and then I couldn’t do much more than wait.

‘Ah . . . there you are,’ said the daitya, inching towards me, wiping the floor behind her with the naga. ‘I’m surprised that you had the courage to stay!’

I leaned back on my elbows, my mind sluggish from the concentrated effort, my body exhausted from the travails of the day.

I was waiting for the storm, of course. The storm that should have been upon us right at that moment if the installation of the gem had worked. The storm that I hoped would be weird enough to get noticed by the man up there. The man in charge. The bringer of rain and the wielder of the thunderbolt. Surely he would notice a freak storm over the land where his attempts to receive critical intelligence reports had failed? Surely he had someone watching, some underling peering down at the city from the heavens, who would be surprised to see a flashing nimbus conjured up in otherwise clear air?

At least that’s what I told myself.

‘Of course, you didn’t quite have the gumption to come out and help your new friend,’ she was saying between guffaws. But she was also panting by now—I could smell the stench of her breath from where I sat unmoving, a room’s length away.

At the back of my mind, rationality persisted in raising doubt. Why would the lord of all weather phenomena all over the world be concerned with a freak storm over a small part of a big city?

‘Pah! Don’t feel guilty, little human. It wouldn’t have done any good. This result was preordained. Now, we have to take the naga scum captive, but we don’t need you around, do we? Oh, little man. Little fool! I can’t wait to hear your wails for mercy!’

And then of course, I thought, there was the fact that a properly installed nagamani brought with it a quantity of fortune for its owner. Wealth and luck, and things in between.

The thunderbolt smashed into the daitya through my window, charring her right side.

She screamed and released the naga, and had just managed to bring both hands up in defence when the second one came through. Her hands offered no protection against the searing flash.

Of the other two daityas, the one who had absorbed the full effect of my charm still lay on the floor. The one who was conscious stared at his comrade who had been burnt to a crisp, and retreated through the door, screaming. I covered my eyes as the lightning flashed again, and the screaming stopped.

Phew.

The man who entered through the freshly demolished side of my house was dressed in all-white—white garments, white armour, white jewellery and a flashy white crown on his head. His hair was also long and white, and his right hand held an object so brilliant I couldn’t really see it.

‘What a terrible piece of business,’ he said, shaking his head. And then, pointing at me, ‘You! How did we get here?’

‘Well,’ I began, ‘it all started when a beautiful woman stepped into my office this morning, claiming to be a naga whose gem had been stolen. She told me she’d been jumped on Vasu’s Way by this really strong man, and that she couldn’t turn back into a serpent without the—’

‘Stop, stop, stop!’ he said. ‘I don’t have the time for all that. Just give me the gist of it!’

So I told him the story from the perspective of the naga spy, who lay face down before us like a discarded rag doll, as best I could. Indra blew out his cheeks impatiently while I spoke, and when I finished, he said, ‘Whatever!’ and whistled as if summoning a pet.

Under the prone naga, an indistinct dark mass began to form, and he was slowly raised about three feet in the air. The thing that was carrying him looked like a dense cloud formation and was shaped roughly like a mattress. Behind them, I saw that a similar construct had been conjured up under the only daitya left alive.

Both unconscious figures began to float up and out of my house on the cloudy platforms, and I was seized with a sudden panic.

‘Wait!’ I yelled, and Indra looked at me with incredulity, stunned that I would dare stop him. ‘His nagamani!’ I indicated the gem that lay within the mandala.

‘Quick!’ said the god-king. I snatched the gem off the floor and stepped over the rubble to get to the naga. I bent over as I placed it beside him on the bed of cloud and made sure that he was still breathing.

‘Step back,’ said Indra, now well and truly annoyed. ‘And try to keep this quiet, all right?’

They blasted off into the sky, and I stared at their contrails long after they’d disappeared into the distance, my hand resting on the jagged edge of the crater in my wall.

I thought about the whole thing a l

ot over the next few weeks. About whether I’d done the right thing in the end by siding with the devas and the nagas against another faction that wanted the same thing—control over everyone else. I mean, none of them really had a stake in how things went in the surface-world. The realm of humans was just a theatre of war for these guys, or a trophy that gathered dust on either team’s shelf between short bursts of intense competition.

I guess in the end my choice of sides was motivated by self-preservation and the fact that one of them had tried to use me to do their dirty work. So I’d let my ego decide what was best for the world, and that didn’t make much sense either.

There were no visible signs of war in the heavens or under the earth. And believe me, I looked. Maybe the devas had got wise to the daityas’ plans before they had ripened, and so the plans had been suspended. Maybe I’d caused a stalemate, which would probably be the best thing to have happened overall.

For days after the incident, I hid from everything. Client visits, city authorities, personal calls and, most importantly, vengeance from anyone who resented my part in all this.

But eventually, life had to go on. I fenced the luminous gems given to me by my daitya client, and used the money to rebuild my office and pay off the city officials when they came around asking questions. I quit looking over my shoulder for superhuman assassins, and set my sights on what lay before me.

After all, I had bills to pay. Monetarily, the whole incident had drained me. Luckily, I found a temporary office in Ojas Madhushala while my old office was being reconstructed. I don’t know how much they knew about the whole issue, but they seemed pretty happy to let me sit there all day, entertaining guests over tall glasses of cold milk. And luckily, I did have several guests, a lot of whom came from places other than the surface of the earth, and each of them had problems weirder than the one who came before.

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale

Tooth and Nail, Fur and Scale